Shirin Ebadi’s Date with Mumbai

A day with Iran’s Nobel Prize-winning human rights lawyer at the 2004 World Social Forum.

Shirin Ebadi looks troubled. She leans forward on a plastic chair, shoulders hunched under her pink suit jacket.

She doesn’t seem to hear the hopefulness in the song a line of school children are singing for her. Instead, she gazes sadly at the rows of giggling girls sitting cross-legged before her on chatais laid over battered concrete.

A controversial Nobel Peace Prize winner and a lawyer specialising in the defence of political prisoners, Ebadi (56) is no stranger to pressure. As an outspoken critic of human rights abuses and repression by the religious government in her native Iran, she has withstood repeated abuse, threats and imprisonment.

But at the Sahyog school for daughters of slum-dwellers rehoused at the Shantiniketan resettlement colony at Dindoshi in suburban Goregaon, her famous toughness falters.

“I want to cry,” she tells her interpreter in Farsi. “I want to cry.”

Pursued by journalists and photographers, Ebadi has taken a morning out of a hectic schedule of World Social Forum conferences, panels and debates to see the plight of the people the forum is supposed to help.

Resettled 18 months ago from the Rafique Nagar slum in Kurla, there are 18,000 people living here, mostly day labourers earning no more than Rs 50-Rs 60 a day. There is no municipal school, no health post, no dispensary, not even a ration shop.

With extra charges imposed on them for maintenance, electricity and water, the community is sinking into debt. A quarter of the children here have dropped out of school, many to work or look after younger siblings.

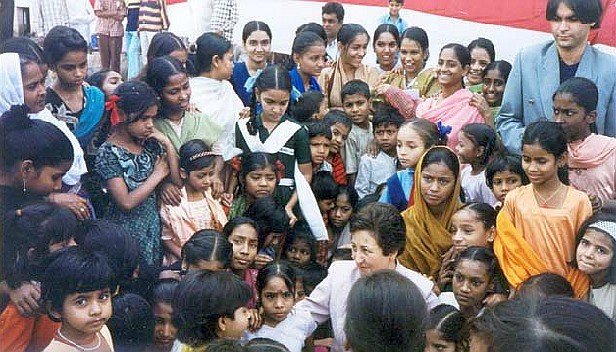

Ebadi’s arrival sends a tremor of excitement through the colony. She is taken to see the school’s single ‘classroom’—a room barely 4 x 5 metres—then led outside to meet the children.

The school, run by local non-governmental organisation Sahyog, has 60 girls, aged 11 to 18. All around are bright saris and brighter smiles, overwhelmed by the arrival of a famous foreign guest and a gaggle of reporters.

Ebadi gives them her first broad smile of the day. Her earlier sadness has been replaced by strength.

“You have to learn that you must take your rights by yourselves,” she says sternly to the rows of wide-eyed faces, punctuating her words with a pointed finger. “Don’t allow anyone to humiliate you or be cruel to you.”

She asks them to mark the anniversary of Gandhi’s assassination, January 30, as an ‘International Day of Non-Violence’ and pray for peace. “In Iran, I will pray for peace with you,” she says.

After her speech, and the promise of a computer for the school, the diminutive Ebadi is nearly knocked off her feet by a rush of excited girls.

“Don’t push! Don’t push!” cries one of her assistants. Every one of the girls wants to shake her hand. Ebadi does so with each one, smiling.

She’s late for a WSF debate and has to leave.

Education, especially of girls, is a subject close to Ebadi’s heart. For her, it’s the key to fighting discrimination against women—something she has first-hand experience of.

The country’s first ever female judge, Ebadi served at the city court of Tehran from 1975 until the Islamic revolution in 1979. The new regime declared that female judges were against Islamic law and demoted Ebadi to role of court secretary. “I couldn’t tolerate it, so I resigned,” she says.

She became the first Muslim woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize in October 2003, an award condemned by Iranian conservatives as a political attack on the regime. But since then, Ebadi’s fame has immeasurably strengthened her position. “They can’t touch her now,” smiles her interpreter, Babak.

After a frenzied drive, she enters the chaos of NESCO Grounds for her next speech. At Hall 4, Ebadi is the guest of honour, opening a debate on human rights.

“Islamic governments discriminate and repress women and they call those who disagree blasphemers,” she tells the 4,000-strong crowd angrily.

Cheers and whistles break out across the hall. But a part of her ire is clearly directed further westward, at governments “who suppress human rights under the pretext of the fight against terrorism.”

It’s over in minutes. Ebadi and her interpreter stand up, to the obvious dismay of the debate’s chair, Irene Khan, Secretary-General of Amnesty International. Ebadi has to attend another meeting.

“It’s not that she doesn’t want to listen to us,” Khan falters into the microphone, “But as you can imagine, she’s very much in demand.”

There’s no time for lunch. Buffeted by a Korean anti-war protest, Ebadi practically sprints to the next panel on ‘The Public-Private Divide’.

She condemns an upcoming French law banning Muslim girls from wearing the hijab in schools. “It will only encourage fundamentalism,” she warns. While other panelists speak, she takes secretive forkfuls of fruit behind her hand to keep her going.

It’s four o’clock before there’s a break for food.

Under the rouge and lipstick, Ebadi looks worn out. “I’m a little tired,” is all she will admit to.

The morning’s school visit still hangs heavily on her mind. “It was so frustrating, deeply frustrating, to see those girls,” she says. “If there was justice in the world they wouldn’t be living like that.”

An assistant leans in. It’s time to go again. Ebadi seems to wilt briefly, then stands up. Four months after winning the Nobel Peace Prize, she still seems unprepared for the demands of international celebrityhood.

“I expected to win it,” she says, with a sly grin. “But when I’m 80, not so soon. I thought it would take a lot more work.”