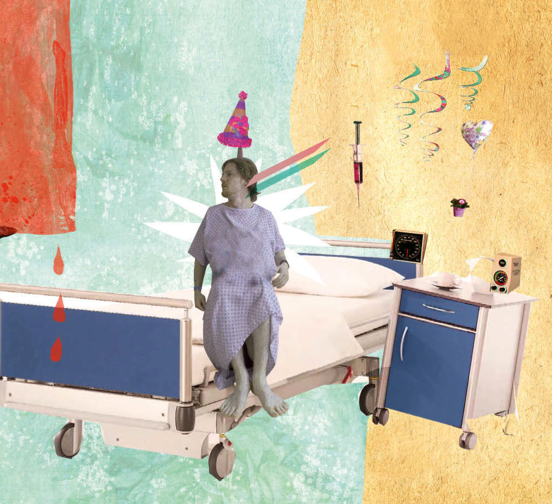

Breakfast Meetings with the Universe

Iain Ball discovers some unexpectedly uplifting side-effects from neurosurgery

When they changed the bandages, I got a glimpse of myself in the mirror.

Half my head was bald. Above my left ear was a raw, four-inch scar. It looked like a punched mouth, stitched shut. I was something out of an ‘80s horror flick. Frankenstein’s monster with a wicked punk hairdo.

It felt like bits of my memory had been snipped out during the surgery. I couldn’t remember the names of friends and colleagues. One morning, I was handed a newspaper. The lead story was very badly written and didn’t make sense. I couldn’t understand who was doing what, when, or why.

The news was: I couldn’t read and write properly.

Although I could still speak and understand English, it was seriously faulty. I called the hospital a hotel, because it began with H and ended with L. I couldn’t remember words for ‘drawer’ or ‘cucumber’ and other everyday things. The world of objects had become a row of tin cans with the labels ripped off.

My doctor assured me the words would come back. The tumour had affected my left temporal lobe, the language centre of the brain. But they’d only had to cut out a small chunk. I would be back to normal within a few months, he said.

I was too exhausted to be worried. Instead, I slept. But it felt like parts of myself had been deleted, not just my memory. And then something strange began to take their place.

There is no language to describe the experience. At least, there’s no language to describe it without sounding like you’re on acid or you’ve just spent six months at a dodgy ashram. Maybe what happened can only be experienced when you don’t have any language. But the morning after I was moved out of the ICU, the sunrise filtered through the curtains into my room, reached across the bed to wake me up, and time stopped.

Blinking in the early light, I reached up and touched the glowing wall above my bed in a state of wonder. Somehow, I could feel that the wall was alive.

In fact, everything in the universe was alive, and all of it had come to visit me in my room. There was no beginning and no end. Everything that ever was and will be had become a single moment of sublime, unconditional love, and the moment was now.

I woke up in the same way each morning for the next two weeks, in a spectacular communion with the ineffable that lasted for an indefinable period of time.

I couldn’t talk about it. So I hid in the bathroom so that people didn’t see me crying – quiet, grateful, unstoppable tears – and by mid-morning, everything would be back to normal.

After lunch, the joy would often be replaced by explosive, exhausted crankiness until I got some sleep.

I finally mentioned it to the neurologist. He looked embarrassed.

‘It’s the left temporal lobe,’ he said. ‘People report strange experiences. I wouldn’t worry about it.’

There wasn’t time to talk about it. He needed to prep me for outpatient radiation therapy, and in the central Mumbai hospital waiting room outside there were dozens of people with far worse problems. I was lucky to have a bed; some cancer patients slept on the street.

I was discharged from hospital. The feeling continued, but was ebbing away, declining in intensity as the names and words came back. One morning, I visited a Croma department store, looking for a new fridge-freezer. Despite all the shiny surfaces, everything seemed drab. It felt like the ineffable had finally effed off.

Historically, foreigners in India have got their spiritual kicks on the hippy trail. I’m the only one I know who got them in hospital. It’s now four years later, and the experience has never returned. I’m still not sure how to categorise it.

As far as I can tell there are three possibilities: They were either side effects of neurosurgery, drugs and stress, or breakfast meetings with the universe, or, somehow, both.

Despite the obvious and easy rational explanations, I just can’t – or maybe I just won’t – rule out the possibilities. It seems like a foolish and self-limiting thing to do, like denying that you’ve fallen in love or are deep in grief.

So I remain agnostic, and I have to leave it open. But whether it was a bump on the brain, or the truth of the universe, I don’t think it matters. Because for a while it seemed as if – beneath all the grinding and the cursing and the blood – everything really and truly is all about love. And that is a blessed memory to have.

In 2018, I took part in a study of mystical experiences and epilepsy conducted by the Faraday Institute and Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, and gave a talk about my experience at The Cambridge Festival of Ideas. That led to this appearance on National Geographic’s The Story of God with Morgan Freeman in 2019.